The Political Dimension of Faith – the Context of Malta

Profs. Oliver Friggieri reflects on faith as a matter of life and its effect on politics in the context of Malta

Can the Constitution ignore a major collective dimension such as faith? Is culture complete without its transcendental component? Is there art which is not intrinsically religious? Is it possible for a political party to claim that it is non-confessional, given that it is granted electoral support for its professed beliefs? Is there a specific point where all contrasting standpoints are equally represented in any document of national import? Does plurality (or pluralism) by definition exclude or include? Can a politician afford to suppress his/her religious convictions in public life? Is faith public or private? Can different religions abide together and consequently express the sentiment of a multicultural community? Which are the limits within which ‘political correctness’ is actually democratic and fair?

Our ancestors, wisdom beyond literacy

Such questions were never put publicly throughout Maltese tradition, a series of essential constant values, and a set of few variables of a much lesser significance. Such questions, namely the ones which are timeless, universal, common to the whole of humanity anytime anywhere. Such is their relevance that all our concerns are ultimately reducible to them. A summative word tells the whole story: survival. A State guarantees survival until death, whereas Faith overcomes the quest for survival from death onwards.

Our ancestors, illitterate and wise, unassuming and proud, people with an inner strength which only solid faith could guarantee, have gone deep down their humble hole in dust unsung, ignored, uncelebrated, even despised, as we do whenever we naively spurn their patrimony, primarily the marvellous language they forged and spoke, and only lately wrote down. But their legacy lives on, and without it, however much we lack a sense of history and consequently a sense of gratitude, we cannot embark on any project which claims recognition on an international level.

They were the ones who could be mentally and verbally so creative as to produce words which transcend the confines of specific cultures. For instance, they produced new Maltese words from Latin and English words: gens (Lat.), ġnus; regula (Lat.), rwiegel; figura (Lat.), fgajjar; kitla (from English kettle), resembling the Semitic word xitla, plural xtieli), ktieli. Such a few instances suffice to suggest to what extent whole generations of Maltese have been creative in such a manner as to fuse two distinct cultures (Latin, Semitic) into a unique one, their own, unconsciously proving that such mental patterns are expressions of a much deeper human urge: coherence. By comparing different generations in such a light, one can methodically identify to what extent the post-modern Maltese brain is losing agelong categories. The present unhappy condition of verbalisation provides the best example of what is happening to being Maltese. The mental system is under siege, and it is reflected in linguistic utterance, but the character of spoken words is indicative of a much deeper reality, which is not verbal at all.

Our educational system still needs to shed off the shackles of colonialism, and join the European Union also in terms of national self-esteem which is so much on demand nowadays even to guarantee continental unity through the only available path: diversity. But we have inevitably matured enough as to recognize the need of historical continuity. We may therefore seek to give our ancestors a tribute now at least by perceiving our modernity through a diacronic, historical perspective. A case in point is the way we may need to discuss their/our ancestral religious character.

A national identity in crisis

It was these people, whom we have traditionally learned to despise so much, who bequeated us this rich heritage of faith and whatever goes with it, from cuisine to architecture, music, art and our own ancient self-consciousness as a distinct nation. It seems Malta has somehow exhausted its political agenda (1. dealing with a challenge called Mintoff; 2. defining the distinction between State and Church; 3. joining Europe), and is now becoming obsessed with its own historical identity. A worrying crisis of identity indeed, in which Malta is risking throwing away the baby with the bath water. A somehow choral reaction is being put up against the basic action of our ancestors who have so graciously and so stubbornly created a wholesome nation out of a tiny barren rock.

This is a collective achievment of numerous generations, and is equally political and religious. Roots have to be nourished, and children have the right and the need to be aware of the past of their ancestors. They are entitled to attain a high sense of belonging. There do faith and culture flourish hand in hand, as they may also collapse together. Malta, however, is lucky enough as to have a Prime Minister and a Leader of the Opposition who regularly show full awareness of such considerations. The President herself is a glaring example of how the country can go on being instinctively true to itself and dutifully respectful towards otherness.

A moral challenge: Collaboration between State and Church

The time has come for our major institutions, political parties, Church, Education Department, who really care about the happiness of our future generations to thoroughly and professionally take stock of the situation. Such analysis must go much beyond opinions and impressions, as structural changes are occurring in a speed and towards directions which warrant attention and cause concern. Educators involved at all levels are by definition the most qualified to assess such a situation.

“The Church still enjoys the adherence of the majority of the Maltese. But the commandment of absolute love, as defined by Our Lord, demands that plurality is guaranteed to any other sector, independently of its numerical import.”

It will be a real pity if such a rich and healthy heritage, moulded according to the dictates of history and to the loyal efforts of our own relatives, is put aside or even foolishly destroyed simply because Malta is somehow going through its teenage crase of questioning all and believing none. Such has been the predicament of many other European countries, with which Malta can be safely compared, and whose velocity of change and development varies accordingly. It looks like a car which has just discovered the clutch, and lost sight of the breaks.

Contemporary Malta seems to be reacting against a whole tradition which even prophets like Dom Mintoff (regarding the Church), George Borg Olivier and Eddie Fenech Adami (regarding the Constitution), notwithstanding their massive support, did not dare ignore. All have graciously added their own contribution to history without in any way despising whatever had been previously acquired. The question whether the Church should go on being a protagonist in the life of Malta is a democratic as much as a religious challenge. The Church still enjoys the adherence of the majority of the Maltese. But the commandment of absolute love, as defined by Our Lord, demands that plurality is guaranteed to any other sector, independently of its numerical import. A Christian believer is bound to be a democrat and is equally expected to love, and never to judge.

The place of God in contemporary culture

The question of God’s place in culture involves national dignity and not simply one’s own private conviction. Faith is equally private and social. Our European cultural bequest is almost exclusively religious. Architecture, literature, music, the visual arts, and all other genres of creativity have been and in various cases still are manifestations of faith. So have been and frequently still are the best brains in the fields of scholarship and thinking. What can be easily concluded regarding Christian faith can be also easily said in the regard of other major religions, such as Islam and Judaism. It can never be otherwise since all this involves the most imperative of human concerns: an explanation of being, and the certitude of permanent survival.

The question of God’s place in culture involves national dignity and not simply one’s own private conviction. Faith is equally private and social. Our European cultural bequest is almost exclusively religious. Architecture, literature, music, the visual arts, and all other genres of creativity have been and in various cases still are manifestations of faith. So have been and frequently still are the best brains in the fields of scholarship and thinking. What can be easily concluded regarding Christian faith can be also easily said in the regard of other major religions, such as Islam and Judaism. It can never be otherwise since all this involves the most imperative of human concerns: an explanation of being, and the certitude of permanent survival.

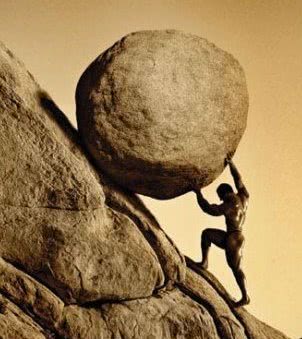

God, always controversial and challenging throughout history, always ultramodern and timeless, will go on provoking reactions typical of the specific era men are going through, since men are, like Sisyphus, doomed to define timelessness in terms of the flimsy span of life which is their own weary stay on this planet, a place demanding answers and frequently only begetting new questions. Where science stumbles, faith takes over serenely, or else it is utter darkness. Computing itself compells us to go beyond whatever is empirical.

Faith in God as a political question

That is why the question of faith in God, an essentially political problem, goes on being challenging to men of culture as much as to politicians. Ambiguity, the ultimate language of God, will go on provoking us to take sides, namely to simplify and run into conclusions, or to keep silent and let the voice of sense speak loudly within us (such as faith, the expression of humility). All of us have ultimately to deal with a question which goes beyond science: why, and not how, do we actually exist. The finest minds of our times, such as Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking, have dealt with this basic need of humankind: to identify a secure point of reference which can in some way render scientific progress meaningful in humankind’s quest for happiness.

We may react to the historical approach this basic truth has had in our own personal lives. We may dislike an aspirin, but we still have to deal with our headache. The Church may have let us down, but the same fundamental principles she stands for still beckon. It will be impossible to get rid of this continuous mental provocation demanding an answer as to why we actually exist. We may be disturbed with our own economical, social, medical problems, but the main concern remains: why do we exist, and where are we going to from here? Indeed, God, love and death are the perennial themes of art, and mainly of literature. We may tend to ignore them now, but we will have to face them sooner or later. As Schopenhauer himself admitted, it is due to death that Philosophy and Poetry exist.

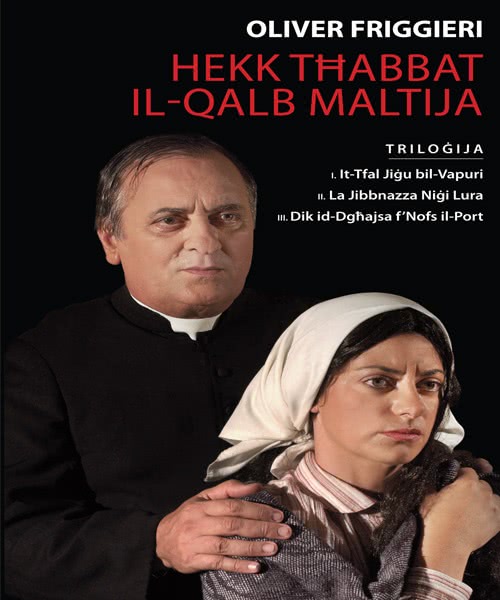

Literature will eventually die out and become extinct if it overlooks the existential challenges of humankind. Technological advancement, a real blessing guaranteeing efficiency, has absolutely nothing to do with the obsessive human quest for post-mortal survival, the main preoccupation beneath all efforts. That is why I thought a trilogy, Hekk Thabbat il-Qalb Maltija, uniting personal preoccupations in a tiny remote Maltese village with the existential quests of all men anywhere at any time, could actually illustrate the conclusion that it is only faith which makes sense out of the absurdity coherently provided by human logic. Existentialism is still the most relevant exposure of the human condition, and we have hardly added anything to what has been so painfully thought by Sartre and other great minds of this era. We can still recognize ourselves in Jean Anouilh’s LeVoyageur sans bagage (1936) and in Sartre’s La Nausée (1938). The so-called ”unchangeability” of the human condition still warrants an explanation and will go on being equally disturbing and unbearable. The perennial ”bundle of useless passions” will go on evoking usefulness. Absurdity demands meaningfulness.

Literature will eventually die out and become extinct if it overlooks the existential challenges of humankind. Technological advancement, a real blessing guaranteeing efficiency, has absolutely nothing to do with the obsessive human quest for post-mortal survival, the main preoccupation beneath all efforts. That is why I thought a trilogy, Hekk Thabbat il-Qalb Maltija, uniting personal preoccupations in a tiny remote Maltese village with the existential quests of all men anywhere at any time, could actually illustrate the conclusion that it is only faith which makes sense out of the absurdity coherently provided by human logic. Existentialism is still the most relevant exposure of the human condition, and we have hardly added anything to what has been so painfully thought by Sartre and other great minds of this era. We can still recognize ourselves in Jean Anouilh’s LeVoyageur sans bagage (1936) and in Sartre’s La Nausée (1938). The so-called ”unchangeability” of the human condition still warrants an explanation and will go on being equally disturbing and unbearable. The perennial ”bundle of useless passions” will go on evoking usefulness. Absurdity demands meaningfulness.

On the other hand, life is also believed to be meant to be transcended. Humankind faces challenges which are both political and existential. Michel Foucault aptly fuses the economical and the existential quests into one whole: were men to solve all earthly problems, the existential question will still loom there to be dealt with. Faith is therefore even older than its being historically ‘outdated’; it is permanent, older than old age itself.

The constitutional challenge

Should the name of God be included in the Constitution? The problem is that the Constitution is too inferior, incidental and transient to include Him. Any Constitution is just a footnote for Him. He actually transcends millennia and prefers to live in the hearts of humankind. He has done so since the beginning and in all civilisations. He is supreme, equally controversial and evident. He is, and His silence is forcefully eloquent.

Is it not intriguing to spend twelve years striving to give shape to this conviction through a novel? Let it be so. Hekk Tħabbat il-Qalb Maltija. This is a noble country because its heart has been consistently noble. Simple, unpretentious, illitterate, lacking recognition in their own tiny Malta, our ancestors were wise enough as to construct such a formidable uninterrupted tradition of faith manifesting itself in all sectors of living. The way they expressed themselves in stone and in words (architecture and language), the most formidable documents of the ancient history of an island colony, explains how they managed to survive as a nation and to discover the transcendental dimension of being. This they accomplished to the point that Malta is what it is due to its religious character, without which it will simply be a desert. Tourism itself largely relies on this fusion of religion and culture. A typically Mediterranean island whose future relies in the proper cultivation of its past, a task demanding both competence and love.

Updated: May 2017

Read more:

– Astronomy and Faith

– Top Popes’ Quotes About Faith